SEVEN TIPS FOR THE HEIRS OF THE INKLINGS

There is no shortage on tips

and recommendations for writing stories in the fantasy genre. Anyone who has an

interest in becoming a fantasy storyteller will already be acquainted with the

tons of guides and suggestion lists for crafting good plots, characters and

secondary worlds. Nevertheless, though there is a lot to be gained from these

helps, there is something that is often missing from them.

Most of these list of

recommendations assume from the outset a very superficial outlook on the

fantasy genre. They assume that fantasy is just like any other modern literary

genre, except that it contains dragons, wizards and magic. This way of looking

at fantasy, however, is severely flawed, as we have proven in other articles

(here). It fails to address the deeper layers of meaning that are inherent in

the genre and allow it to be so distinctively fascinating. Therefore, by

adopting a view of fantasy that is awfully superficial, modern guides for writing

fantasy have fostered the identity crisis of the genre despite all the good

technical advice they may provide new storytellers with.

Yet as we saw in a previous

article, this doesn't mean that there is no solution to the identity crisis of

fantasy. If there is one way that the genre can be saved from the depths of

this crisis, it is by returning to the great tradition that gave birth to it,

and that tradition is found in the Inklings.

But alas, if anyone would

desire to follow in the steps of Barfield, Williams, Lewis and Tolkien, he will

be disappointed to find that there are little to no resources that may guide

him through the process. That's the ill this humble article proposes to amend.

In the course of this article, we will provide seven brief suggestions for

those aspiring heirs to the Inlikings tradition. God-willing, by the time

he has finished reading, the reader will have found a light to guide him

through the dark.

1. Familiarize yourself with

myth and fairy tales

If one wants to become like

the Inklings, he must be acquianted with those tales that brought the

Inklings together. This is why fairy tales and myths are a crucial part of

forming oneself as an heir of the Inklings tradition. After all, the club initially

got started as a place to read and enjoy together myths, legends and fairy

tales. Had it not been for the great legends of the noble Hector, the

valiant Gawain and the fierce Beowulf, the Inklings would have likely never had

a reason for knowing each other. In other words, these stories formed

the core of their companionship, so it would certainly be imprudent for anyone

who wants to be an Inkling as well to not become familiarized with them.

2. Make the Transcendent a

central part of your writing and your life

The Inklings were highly

spiritual men. None of them would fit the bill for the modern or postmodern

writers of today, and that is partly what makes them so great. Their insight

into the transcendent side of reality is not only fascinating but also deeply

enriching for their readers. They told stories full of meaning that

brought back Beauty and the Divine to a world that had forgotten these

realities.

Hence, if one is to follow in

the footsteps of the Inklings, he should adopt this transcendent and highly

spiritual worldview in both his work and his personal life. Stories cannot be

about mundane, superficial situations. Rather, they must be about the most

transcendent things in reality, the stuff of epics. But this cannot be

accomplished unless one personally understands the significance that

transcendence has. For this reason, it is crucial that the storyteller

himself, like the Inklings, lives out in his life the spiritual and religious

reality that he depicts in his work. After all, one cannot give what he does

not possess in the first place, and if one wants his work to be transcendent,

it follows that his life should be transcendent as well. It is only be making

spiritual and religious transcendence the center of one's work and life that

one can honor the heritage of the Inklings.

3. Know your culture, love

your culture and write about your culture

When the Inklings wrote their

works, they did not draw their inspiration out of a sheer romantic feeling of

self-expression. On the contrary, their inspiration was anything but emotive

self-expression. Rather, one of their main sources of inspiration was often

their deep and intense love for their culture. We see this Tolkien when he

declares that he intended his Legandarium to be a sort of mythology for English

culture. We see it with Barfield who could have never written a work like Poetic

Diction had he not first fallen in love with the great poetic

traditions of the old world. And lastly, we see it in Lewis whose love for

medieval and ancient cosmology inspired him to write the Space Trilogy. Thus,

it was their knowledge and love for their cultural heritage that inspired the

Inklings to sub-create.

So if one wishes to become an

Inkling, it follows one must do likewise in this sense. Culture and tradition

must be a treasure for us, not old skeletons we lock up in the attic. They must

be the wellspring from which our writing is nurtured. Furthermore, it's also a

great opportunity to make one's writing intensely personal without falling into

the trap of subjectivism. Suppose you are a Catholic of Spanish and Italian

descent who wants to write in this tradition. Learning about your heritage and

traditions as an Italo-Spanish Catholic will not only give you good resources

to base your work on but it will also give your writing a certain flavor that

is distinctly yours. Those are the advantages of following the path of the

Inklings when it comes to culture.

4. Learn your metaphysics and

theology and incorporate it into your writing

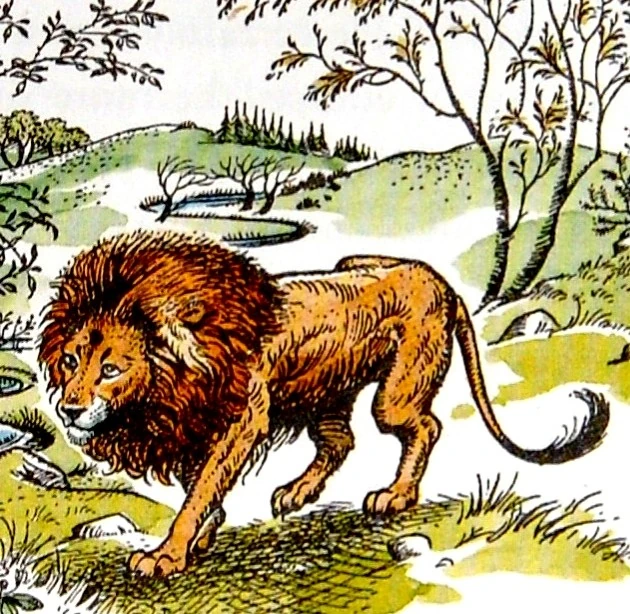

Anyone who has read the

Inklings' work will know that their writing is deeply imbued in classical

metaphysical and theological realities. One need only to look at Tolkien's The

Silmarillion, Williams' occult novels and Lewis' last Narnia volume to know

this. You cannot escape the supernatural and preternatural when you venture

into the Inklings because, in many ways, that was and is the foundation of

their work. But in addition to making metaphysics and theology a central aspect

of their writing, these men also knew enough about these complex subjects to

swiftly incorporate many metaphysical and theological into the plots and

characters of their stories. Many examples come to mind: the most prominent

would probably be Eru Illuvatar and his angelic host of Valar and Maiar and Aslan

and his mystical dominion over Creation. Only men educated in the great

philosophical and theological tradition of Christendom would have been able to

accomplish such a feat. Thus, we get the level of depth that all of the

Inklings' work has.

Therefore, if one wishes to

emulate the Inklings in this respect, he must immerse himself in the

metaphysical and theological realities of the world. First, he must educate

himself on the great philosophical and theological tradition of Christendom.

Secondly, he must analyze and plan how he can incorporate metaphysical and

theological elements into his writing in a way that will give a deep

consistency to the whole mythic story. And lastly, he must practice. He must

put pen to paper and try his hand at writing stories that are profoundly

metaphysical and theological. It's a technique that even the most literate of

Christian theologians and philosophers would have some trouble with. Hence, by

learning, thinking and practicing, the aspiring heir to the Inklings will have

had enough training to imbue his tales with as much as metaphysics and theology

as the great masters did.

5. Develop the secondary

world

Developing secondary worlds,

or worldbuilding (as it is today known), was key to the mythic stories of the Inklings.

These secondary worlds had a rich development, which had a good and consistent

metaphysical and theological foundation. Hence, relying on the last suggestion,

the man aspiring to be like the Inklings must work on his transcendent

foundations to build a secondary world that is filled with layers upon layers

of development. In other words, he should not neglect the worldbuilding of the

setting, as some modern fantasy writers do. On the contrary, he must work on it

as much as he works on the characters and on the plot.

6. Practice immersion,

recovery, escape and consolation

As Tolkien explains in his

essay On Fairy Tales, fantasy that immerses the reader in an enchanted

sub-created world exists for the purpose of three things: recovery, escape and consolation.

Let us explain what is meant by these terms. Firstly, recovery is the principle

by which we see mundane, normal things in a refreshing and enchanting light.

Then, escape refers to the escape from the modern world and into a world that

is more real, more magical and sacramental. And lastly, consolation is that

quality of the tale that brings Hope and Joy to the reader. In other words, it

is the quality proper to the eucatastrophe, that is, the good catastrophe. When

all seems lost and dark and it seems that evil and sin will prevail, Hope and

Joy must arrive to save the day and thus give the consolation of the happy

ending. These are, according to the great Inkling tradition, some of the most

fundamental aspects of good fantasy writing. (You can see a more in-depth

explanation of these three aspects of fantasy here)

Hence, it follows that those

who want to take up the mantle from the Inklings must follow Tolkien's

principles and apply them to their writing. Through their immersive stories set

in wonderful secondary worlds, they must achieve the three things at which fantasy

is best. Accomplishing recovery, escape and consolation in the story means true

success.

7. The story must have as its

ultimate end the echoing of the True Myth

All of the Inklings believed

in what they called the True Myth. This is the Myth that came into the Primary

World and united myth with History. This is Christianity. If anything can be

described as the deepest point of connection for the Inklings, it is this.

That was the ultimate end of

all their stories (to echo the True Myth and thus bring people closer to the

Saving Grace of Jesus Christ), and therefore, it should be our ultimate end as

well. We do not familiarize ourselves with myths for nothing; we do not go

to encounter transcendence in our lives for nothing; we do not study metaphysics

and theology for nothing; we do not fall in love with our culture for nothing;

in short, we do not tell stories for nothing. All this we do for ultimately one

purpose: to grow closer to the God that creates us and loves us and to bring

others closer to Him Who is Love Itself. That is why the Inklings wrote what

they wrote in the end, and that should be the reason why we write as well.

Christ is our beginning and our end, our Alpha and Omega, and more so when it

comes to storytelling.